The Probability of a Matching Game

If a player performs perfectly in a matching game, how many turns will they need to win?

The Matching Game

Consider a game which features \(n\) distinct pairs of colored cards. Each card has one side that is the same across all cards; the colored side is face-down, on a table. Every turn you view two cards from the table; if the card colors match, the player removes them from the table, otherwise they are put back on the table face-down. Using some memorization skills the player continues taking turns until there are no cards on the table. The score each game is the number of moves for completion where a lower score is a better one.

Performance in the game is determined by the player’s ability to remember where certain cards are located and their luck when choosing cards to view.

This game may be called concentration and it is worth familiarizing yourself with the game:

Playing with perfect memory

Let’s examine how well a player with perfect memory would perform. Whenever this player views a card, they never forget it; they play as if any viewed cards become permanently face-up. On any one turn the player would do the following (choosing each unviewed card with equal chance):

- If there are two cards with the same color that have been viewed, choose the pair and remove the cards from the table. Otherwise, pick a first card to view: A player with perfect memory should always choose a card that they have yet to view, since viewing a previously seen card gives no extra information or advantage.

- Pick a second card to view.

- If the first card chosen has a matching card that the player has seen before, then the matching card should be chosen for the second part of the turn. Two cards are then removed from the table.

- If the player has not previously seen the color of the first card they should choose another unseen card to view:

- If the second card viewed contains an unseen color, then the turn is over and the player has added 2 cards to their memory.

- If the player is particularly lucky, the second card viewed could be identical to the first one chosen on the turn, and the player removes two cards from the table.

- If the second card chosen has a previously seen color, but it is not identical to the card chosen in the first half of the turn, then the turn is over, but they player has added two cards to their memory and now has a pair to complete the following turn.

To minimize the number of moves for completion, a player should avoid failing moves. A failing move is any move that does not result in a completed pair. Since only one pair can be removed per turn, a minimum of \(n\) turns are required to complete the game. The difference between the move count and \(n\) is the failure count.

The game becomes much easier with a perfect memory. Give it a try:

Encoding as a Markov Chain

On most turns a perfect player still has to make a random guess for a matching card. Despite playing optimally, performance is still subject to chance. However, we can encode the matching game and the perfect player’s strategy as a Markov chain giving a framework for evaluating the likelihood of a strong performance. Markov chains are defined with a set of states \(S\), and a function \(P(i,j)\) which is the probability of the system moving from state \(S_i\) to state \(S_j\). Each step results in a vector of probabilities that dictate the chance the system is in each state. Markov chains exhibit the Markov property, where the next state of the system is dependent only on the current state, not any state before.

Let the number of distinct card colors in a player’s memory and the number of unknown cards be denoted as \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), respectively. Let \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) be the colors of the first and second cards chosen on the players turn, respectively. Let \(M\) be the set of card colors that the player has seen but not completed a pair for, i.e. \(\alpha \equiv \vert M \vert\). When a new game has started, \(\alpha=0\) and \(\beta=2n\) and we set our initial state \(X_0 = (0, 2n)\).

When there are still unseen cards (\(\beta > 0\)) we can break down state changes and probabilities from player moves as follows:

- The first chosen card’s color is in memory so a pair is completed:

\(\begin{aligned} P(X_{t+1} = (\alpha - 1, \beta - 1 ) \vert X_{t} = (\alpha, \beta)) & = P(c_1 \in M) \\ & = \min\left(\frac{\alpha}{\beta}, 1\right) \end{aligned}\)

- \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) both decrease by 1, as we have removed a single color from memory and its pairing card from the set of unviewed cards.

- As the complement, the probability that a first chosen card has an unseen color is \(P(c_1 \notin M) = \left(1 - \min\left(\frac{\alpha}{\beta}, 1\right)\right) = \max\left(0, 1 - \frac{\alpha}{\beta}\right)\)

- The first chosen card’s color is NOT in memory but the second chosen color happens to be the same:

\(\begin{aligned} P(X_{t+1} = (\alpha, \beta - 2) \vert X_t = (\alpha, \beta)) & = P(c_1 \notin M \cap c_1 = c_2) \\ & = \max\left(0, 1 - \frac{\alpha}{\beta}\right) \left(\frac{1}{\beta - 1}\right) \end{aligned}\)

- \(\beta\) decreases by 2 since two cards are removed from the set of unviewed cards. \(\alpha\) is unchanged as the color that would have been added to memory is removed immediately.

- The first chosen color is NOT in memory and the second chosen color is also NOT in memory (but not the same as the first chosen card):

\(\begin{aligned} P(X_{t+1} = (\alpha + 2, \beta - 2) \vert X_t = (\alpha, \beta)) & = P(c_1 \notin M \cap c_2 \notin M \cap c_1 \neq c2) \\ & = \max\left(0, 1 - \frac{\alpha}{\beta}\right) \left(1 - \frac{\alpha+1}{\beta - 1}\right)\end{aligned}\)

- \(\alpha\) increases by 2 and \(\beta\) decreases by 2 as two previously unseen colors are added to the memory set.

- The first chosen color is NOT in memory but the second chosen color IS in memory so the subsequent turn results in a completed pair:

\(\begin{aligned} P(X_{t+1} = (\alpha + 1, \beta - 2) \vert X_t = (\alpha, \beta)) & = P(c_1 \notin M \cap c_2 \in M) \\ & = \max\left(0, 1 - \frac{\alpha}{\beta}\right) \left(\frac{\alpha}{\beta - 1} \right)\end{aligned}\)

- After this turn \(\alpha\) increases by only 1 as we found a new color but the second card color was already in memory. However, \(\beta\) decreases by 2 as there are now two less unknown cards. This discrepency is confusing as we define the state of our system in terms of the number of colors seen and the number of cards not seen.

Some base/special cases need to be defined when \(\beta = 0\) i.e. when every card has been viewed by the player:

- \(\alpha > \beta = 0\): If none of the cards are unseen, we keep completing pairs until we’ve completed the game.

- \( P(X_{t+1} = (\alpha - 1, 0) \vert X_t = (\alpha, 0) ) = 1\)

- \(\alpha = \beta = 0\): The game is complete. Our score is the number of moves to reach this state.

- \( P(X_{t+1} = (0, 0) \vert X_t = (0, 0)) = 1\)

The cases defined for \(\beta > 0\) above are actually the cases for \(\beta > 0\) and \(\alpha + \beta\) is even. Notice the first three cases keep the sum even. The last case however increases \(\alpha\) by 1 and decreases \(\beta\) by 2 giving an odd sum. This defines our last case which gives a complete partition over the state space:

- \(\beta > 0 \) and \(\alpha + \beta \) is odd: During any given turn \(\alpha + \beta\) should be even because we start with \(2n\) cards and when we remove cards in pairs. Because alpha is the number of distinct colors seen, if we know the location of two cards of the same color, \(\alpha\) only counts one of them, so the sum, which usually represents the total number of cards left in the game, becomes odd. When this case occurs, we immediately remove the pair in the following turn and go back to an even sum.

- \( P(X_{t+1} = (\alpha - 1, \beta) \vert X_t = (\alpha, \beta)) = 1 \)

Example:

It may be easiest to understand the Markov chain by example. Consider the case for a game with \(n=2\) pairs. We have five states in this game \(S = \{(0, 4), (2,2), (1, 1), (0, 2), (0, 0)\}\). We start the game at \(S_1 = (0,4)\) as there are four unviewed cards on the table. There is a \(1/3\) chance we move to state \(S_4 = (0,2)\) (luckily completing a pair on the first turn) and a \(2/3\) chance we move to state \(S_2 = (2,2)\) (choosing two cards of different colors on the first turn). The entire transition matrix looks like this:

\[P(i, j) = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 2/3 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \tag{1}\]Where entry \(P(i,j)\) is the probability to move from state \(S_i\) to state \(S_j\). The transition matrix increases quickly in dimension as the \(n=3\) case has 10 rows and columns with state space \(S = \{(6,0), (4, 2), (1,3), (3,2), (2,1), (0, 4), (2,2), (1, 1), (0, 2), (0, 0)\}\). In fact, the transition matrix for an \(n\) pair game has \(n^2 + 1\) rows and columns. With the transition matrix well-defined, we can calculate the distribution on the number of turns the perfect player will use to complete the game. Although the state space grows quickly as we add pairs to the game, the transition matrices have very few non-zero elements and are also strictly upper triangular, giving indication of high computational feasibility when performing analysis on the Markov chain.

\[P(i, j) = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 4/5 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1/5 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1/2 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/6 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 & 0 & 1/3 & 1/3 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 2/3 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\]Below we have a visualization of the Markov chain for games of different sizes, where points on the plot determine the state with completion at the origin (\(\alpha\) on the x-axis and \(\beta\) on the y-axis), the color of nodes determining how many cards are needed at the start of the game for this state to exist, and the color of links determining the probability to change from the state on one end of the link to the other. When hovering over a state, the states that are reachable in the next from this state are highlighted along with the probability to move to this state. States that can travel to the hovered state will display the probability they have to reach that hovered state.

Results

With the computed transition matrix \(P\) we can use some well-known facts about Markov chains to understand the perfect player’s results. Our Markov chain ends when the game is complete i.e. the state is \((0,0)\). Once in this state, the player never leaves; this is an absorbing state. Absorbing states have some nice properties that allow for an easy computation to find the expected number of steps to reach them. The transition matrix of a Markov chain with absorbing states can be written in the following form [1] :

\[P = \left(\begin{array}{c|c} \mathbf{Q} & \mathbf{R} \\ \hline \mathbf{0} & \mathbf{I} \\ \end{array}\right) = \left(\begin{array}{cccc|c} 0 & 2/3 & 0 & 1/3 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \hline 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array}\right) \tag{2}\]Where \( \mathbf Q \) is a square matrix describing the state transitions between non-absorbing states, \(\mathbf{R}\) is a vector of probabilities for non-absorbing states to move into absorbing states, and \(I\) is an identity matrix with a dimension equal to the number of absorbing states. Using \((1)\) as an example, we see that we will only have a one-dimensional identity matrix as there is only one absorbing state. The vector \(\mathbf{R}\) shows that we can move into the absorbing state when we are in states \((2,0)\) or \((1,1)\) i.e. there are two cards left on the table.

This form allows us to calculate the fundamental matrix, \(\mathbf N = (\mathbf I - \mathbf Q)^{-1} \). This matrix allows us to find the expected number of steps to complete the game when starting from a given state with the formula \(\mathbf{N}\mathbf{1}\) where \(\mathbf{1}\) is the vector of all ones. Although matrix calculations can be expensive, this calculation is relatively inexpensive as sparse matrix calculations on the resulting triangular matrix are very efficient. Using \(\mathbf Q\) as it is defined in \((2)\) we find the expected number of steps to complete the game starting with two pairs is the first element of:

\[(\mathbf{I - Q})^{-1} \mathbf{1} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & -2/3 & 0 & -1/3 \\ 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}^{-1} \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}\] \[= \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2/3 & 2/3 & 1/3 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 8/3 \\ 2 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]Therefore for a game starting with 2 pairs, the expected number of moves is \(8/3\). Because at least 2 moves are required to finish the game, the expected number of failures is \(2/3\). Continuing these calculations for we have the results for the first 10 non-trivial games:

| Number of Pairs to Start Game | Expected Number of Failing Moves |

|---|---|

| 2 | \(\approx 0.667\) |

| 3 | \(\approx 1.333\) |

| 4 | \(\approx 1.923\) |

| 5 | \(\approx 2.552\) |

| 6 | \(\approx 3.162\) |

| 7 | \(\approx 3.779\) |

| 8 | \(\approx 4.393\) |

| 9 | \(\approx 5.008\) |

| 10 | \(\approx 5.622\) |

| 11 | \(\approx 6.236\) |

These results match the exact results that were produced in a StackExchange post. Although we did numerical calculations, it has been shown the expected number of failures is \((2 - 2\ln(2))n + 7/8 - 2\ln(2) \approx 0.61n \) [2] . The paper calculates the expected number of failures, but not necessarily for the entire distribution of outcomes.

Below we have a visualization describing the distribution on the number of failures required to complete a game for the perfect player. Most games are completed within a couple turns of the expected number of turns:

In conclusion, we have that playing the game perfectly will almost always result in completing the game in about \(1.61n\) moves with little deviation from this value. We’ve shown a framework for calculating the distribution on the number of moves required to complete the game and given a computational understanding of a simple card game. For another case study on Markov chains and games of chance see this excellent article on Chutes & Ladders.

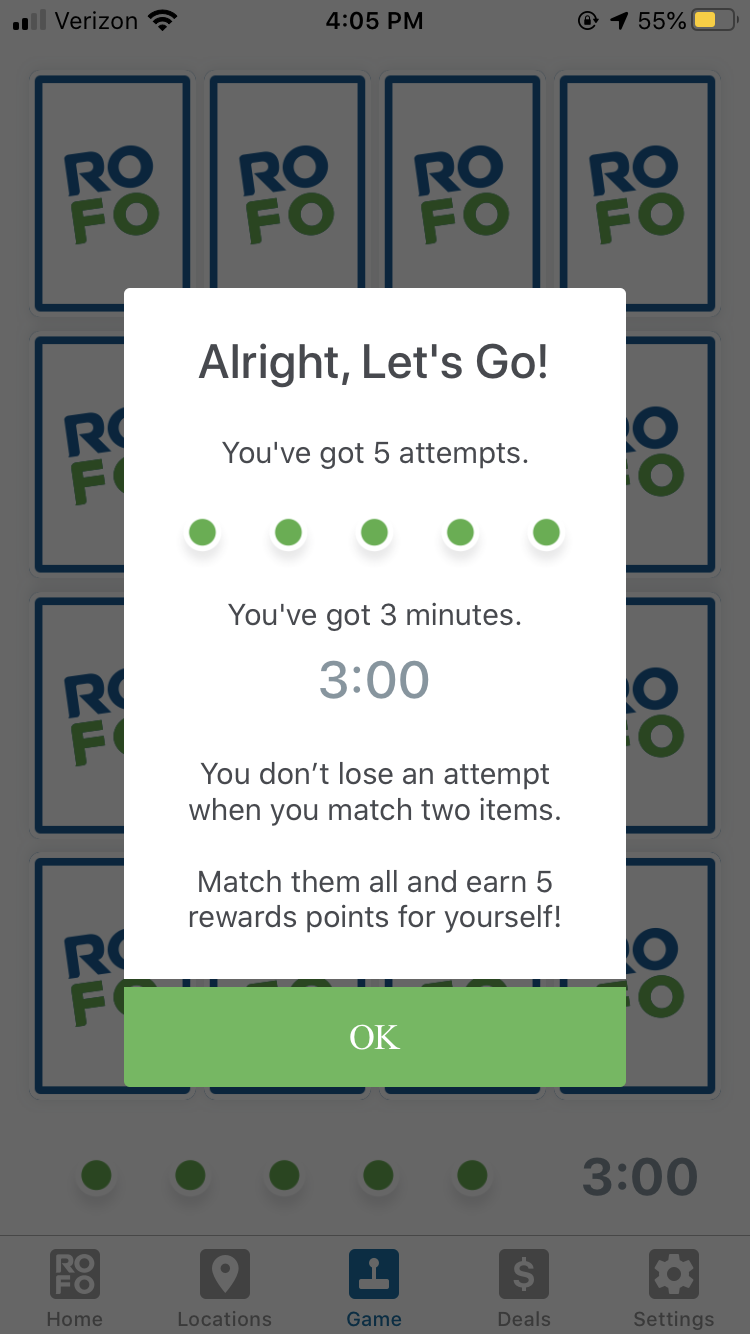

Bonus: The Royal Farms Reward Game

The Royal Farms iOS app has a matching game for users where the reward for completion is some number of points that lead to product rewards.

I wrote this article in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, so to check if Royal Farms was open late at night I downloaded their app. I was inspired to look into this problem since the game struck out to me – is it fair to expect a user to complete the matching game with less than 5 failing moves? The game has 8 initial pairs, so by our calculations the expected number of failures to complete the game is about 4.39. Continuing our calculations, we find the chance to finish the game with less than 5 failing moves is about 55%, if the user plays perfectly.

Sources

- Charles Miller Grinstead & J. Laurie Snell (2006) Introduction to Probability (2nd Ed.), Chapter 11: Markov Chains 416-422

- Daniel J. Velleman & Gregory S. Warrington (2013) What to Expect in a Game of Memory, The American Mathematical Monthly, 120:9, 787-805, DOI: 10.4169/amer.math.monthly.120.09.787

Appendix

Code used to create the visualizations can be found here.

The code used to do the processing of the Markov chains can be found here.